Content

- 1 Understanding PET Degradation Catalysts

- 2 Enzymatic PET Degradation Catalysts

- 3 Chemical Catalysts for PET Degradation

- 4 Mechanisms of Catalytic PET Degradation

- 5 Factors Affecting Catalyst Performance

- 6 Applications in PET Recycling and Waste Management

- 7 Comparison of Catalyst Types

- 8 Recent Innovations and Breakthrough Technologies

- 9 Economic and Environmental Considerations

- 10 Implementation Challenges and Solutions

- 11 Future Directions and Research Opportunities

Understanding PET Degradation Catalysts

PET degradation catalysts are specialized substances that accelerate the breakdown of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), one of the most widely used plastics in packaging, textiles, and consumer products. These catalysts work by lowering the activation energy required for breaking the ester bonds in PET polymers, transforming them into smaller molecules that can be reused or safely biodegraded. As global plastic waste continues to accumulate, with millions of tons of PET entering landfills and oceans annually, the development of efficient degradation catalysts has become crucial for sustainable waste management and circular economy initiatives.

The primary types of PET degradation catalysts include biological enzymes, chemical catalysts, and hybrid systems that combine multiple approaches. Biological enzymes have garnered significant attention due to their specificity, environmental friendliness, and potential for operation under mild conditions. Chemical catalysts, while often requiring more extreme conditions, can offer faster reaction rates and complete depolymerization. Understanding the mechanisms, advantages, and limitations of each catalyst type is essential for selecting the appropriate technology for specific applications in recycling and waste remediation.

Enzymatic PET Degradation Catalysts

Enzymatic catalysts represent the most promising frontier in sustainable PET degradation. These biological molecules, produced by microorganisms, specifically target the ester bonds in PET chains, breaking them down through hydrolysis reactions. The discovery of PET-degrading enzymes has revolutionized approaches to plastic recycling, offering environmentally benign alternatives to traditional chemical methods that often require high temperatures, pressures, and harsh chemicals.

PETase Enzymes

PETase is a hydrolase enzyme first discovered in the bacterium Ideonella sakaiensis in 2016. This enzyme catalyzes the hydrolytic cleavage of PET into mono(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalic acid (MHET) and smaller oligomers. PETase operates optimally at temperatures between 30-40°C, making it energy-efficient compared to thermochemical methods. The enzyme's active site contains a catalytic triad of serine, histidine, and aspartate residues that work together to break ester bonds. Researchers have engineered improved PETase variants with enhanced thermal stability, increased catalytic efficiency, and broader substrate specificity. Some engineered versions can degrade PET up to three times faster than the wild-type enzyme and maintain activity at temperatures approaching 70°C, closer to PET's glass transition temperature where the polymer becomes more accessible.

MHETase Enzymes

MHETase works in tandem with PETase to complete the PET degradation process. While PETase breaks PET into MHET, MHETase further hydrolyzes MHET into the basic monomers: terephthalic acid (TPA) and ethylene glycol (EG). These monomers can then be purified and repolymerized to create virgin-quality PET, enabling true circular recycling. MHETase exhibits high specificity for MHET and demonstrates optimal activity at similar temperature and pH ranges as PETase. Recent studies have shown that creating fusion proteins combining PETase and MHETase domains can significantly accelerate the overall degradation process by facilitating substrate channeling, where the product of one enzyme is immediately processed by the adjacent enzyme without diffusing into the bulk solution.

Cutinase and Lipase Enzymes

Cutinases and lipases represent broader classes of esterase enzymes that can degrade PET, though typically with lower efficiency than specialized PETase enzymes. Cutinases naturally degrade cutin, a polyester found in plant cuticles, and their structural similarity to synthetic polyesters allows them to act on PET. Thermobifida fusca cutinase (TfCut) has been extensively studied for PET degradation and shows activity at elevated temperatures up to 60°C. Lipases, which typically break down fats and oils, can also catalyze PET hydrolysis, particularly when the polymer is in an amorphous state. These enzymes offer the advantage of being commercially available and well-characterized, making them accessible starting points for developing PET recycling processes before transitioning to more specialized enzymes.

Chemical Catalysts for PET Degradation

Chemical catalysts provide alternative pathways for PET degradation, often achieving complete depolymerization faster than biological methods. These catalysts typically facilitate reactions such as glycolysis, methanolysis, hydrolysis, or aminolysis under controlled conditions. While they generally require higher temperatures and more energy input than enzymatic processes, chemical catalysts can handle contaminated or mixed plastic waste streams more effectively and offer greater flexibility in reaction conditions and product outcomes.

Metal-Based Catalysts

Metal-based catalysts, including zinc acetate, manganese acetate, cobalt acetate, and titanium-based compounds, are widely used in PET glycolysis processes. These catalysts coordinate with the carbonyl groups in PET ester bonds, polarizing them and making them more susceptible to nucleophilic attack by glycols. Zinc acetate is particularly popular due to its high catalytic efficiency, relatively low cost, and ability to produce high-quality oligomers and monomers. Recent developments have focused on nanostructured metal catalysts that offer increased surface area and improved mass transfer properties. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) containing zinc, zirconium, or titanium centers have shown exceptional performance in PET degradation, combining high activity with recyclability and reduced metal leaching into products.

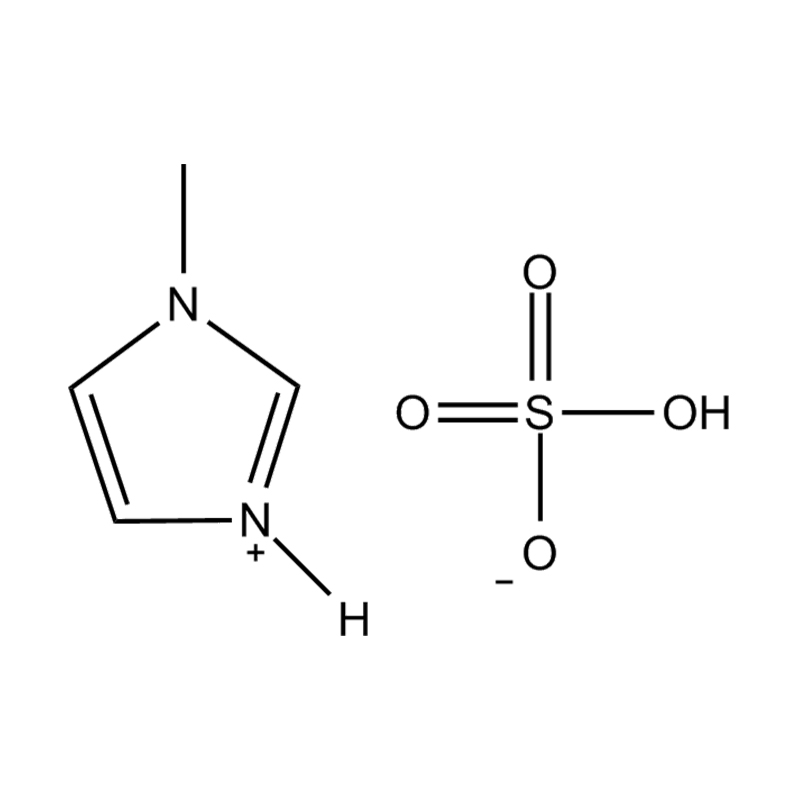

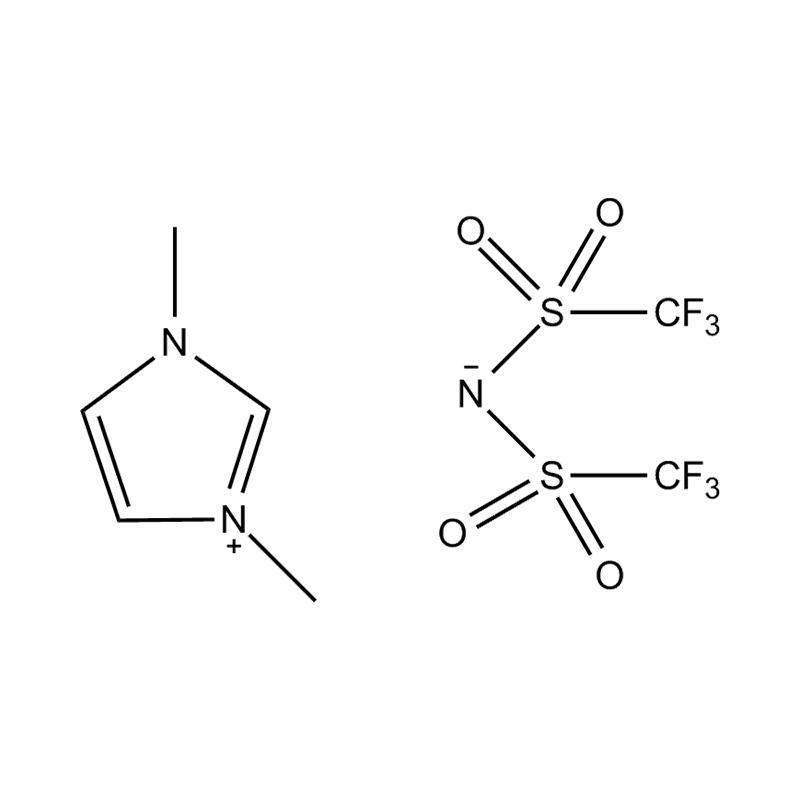

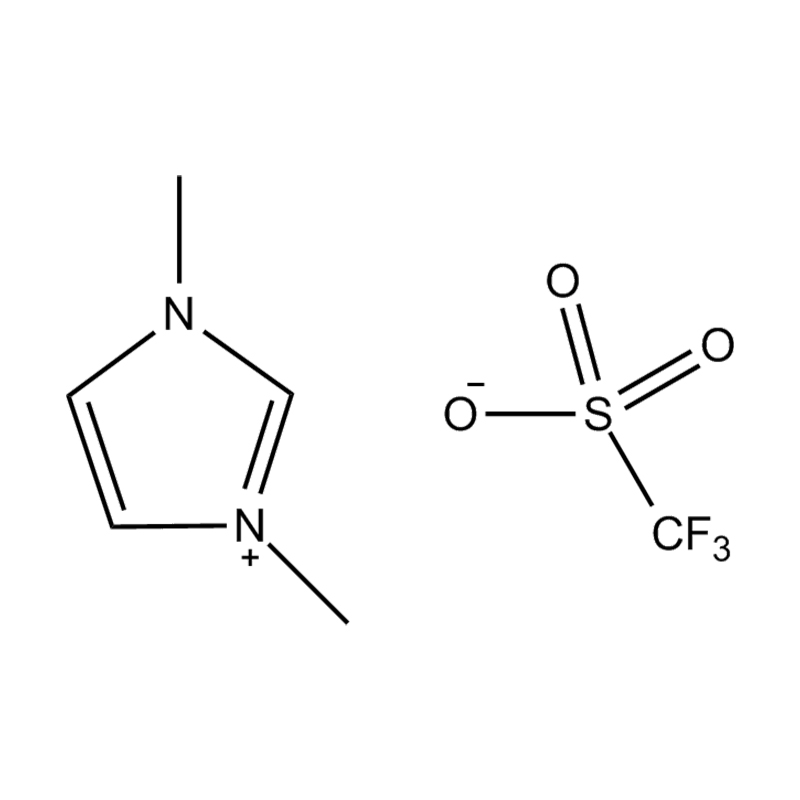

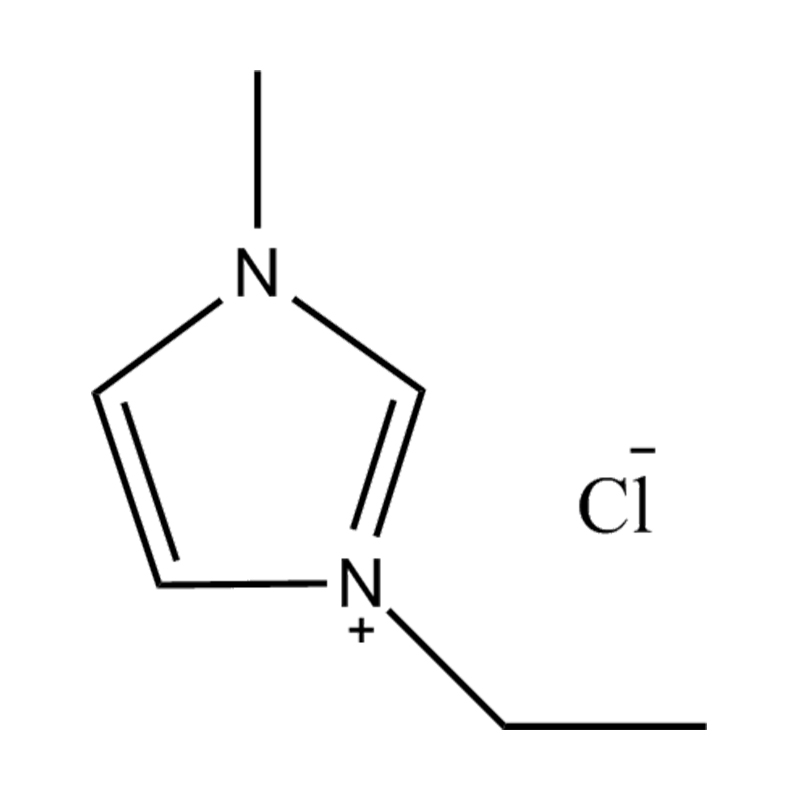

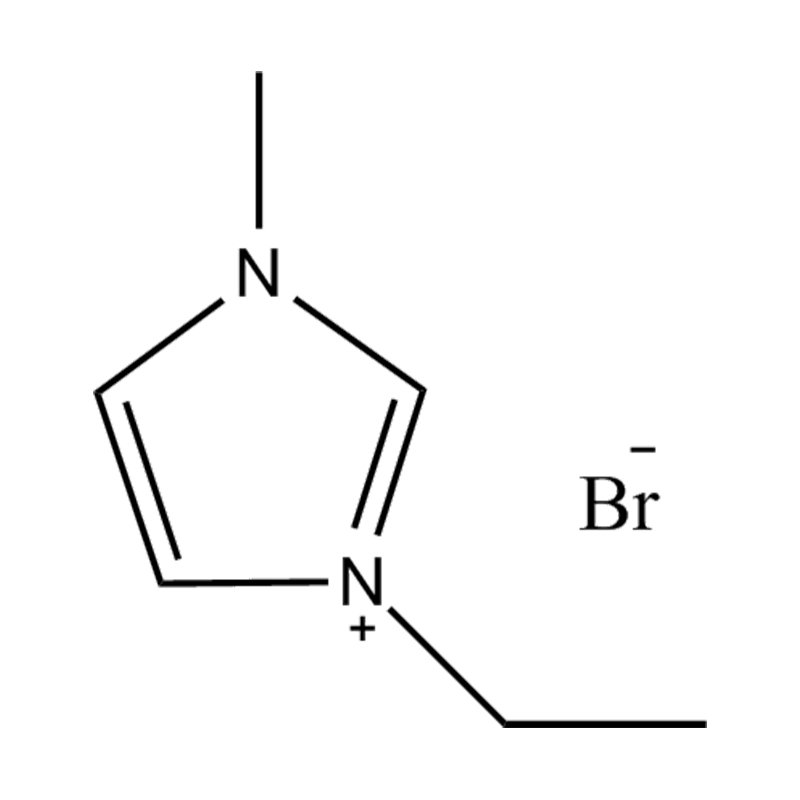

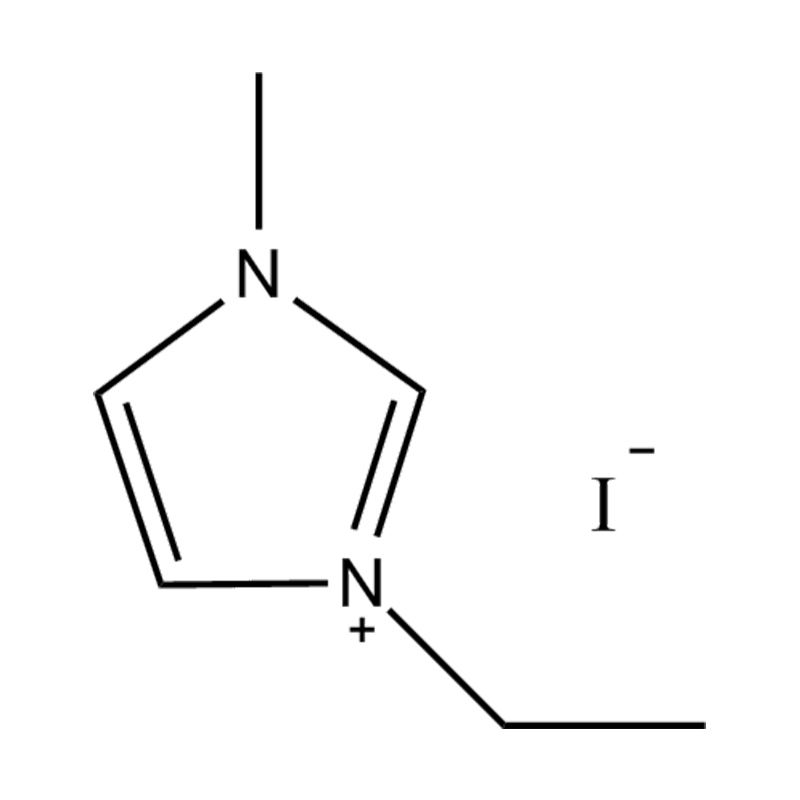

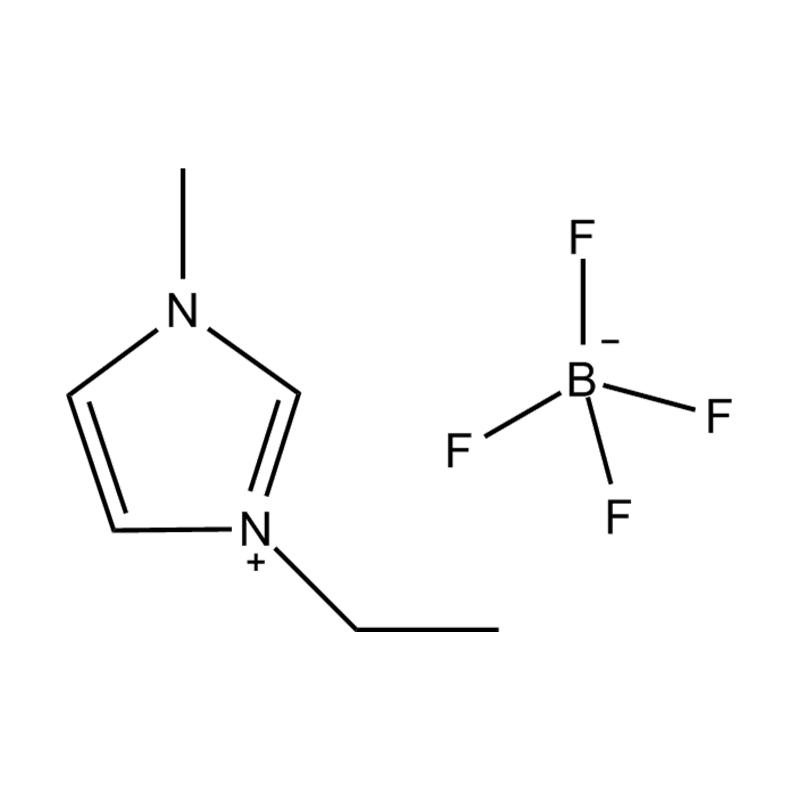

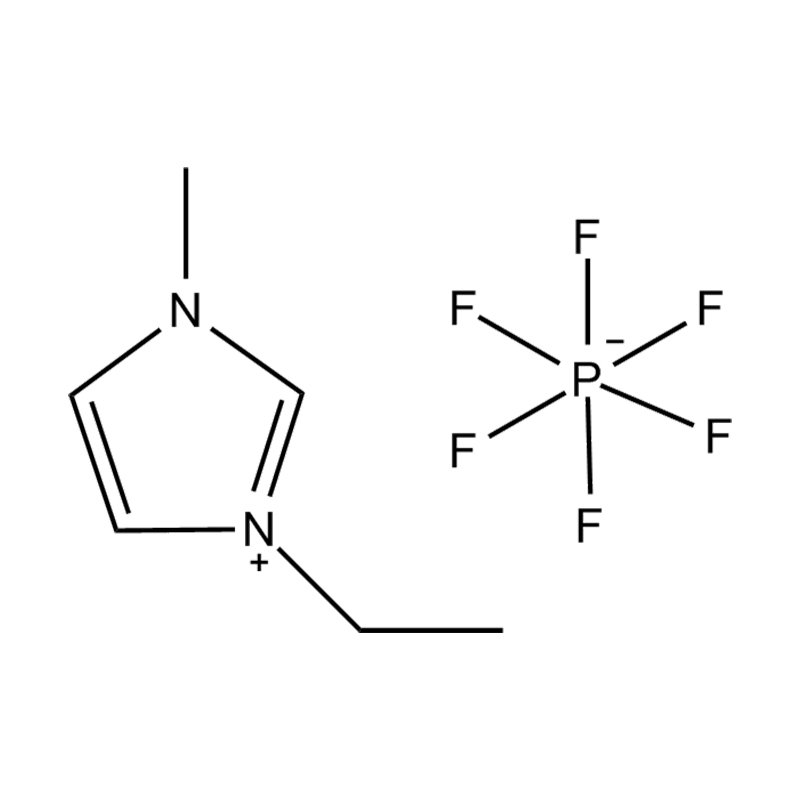

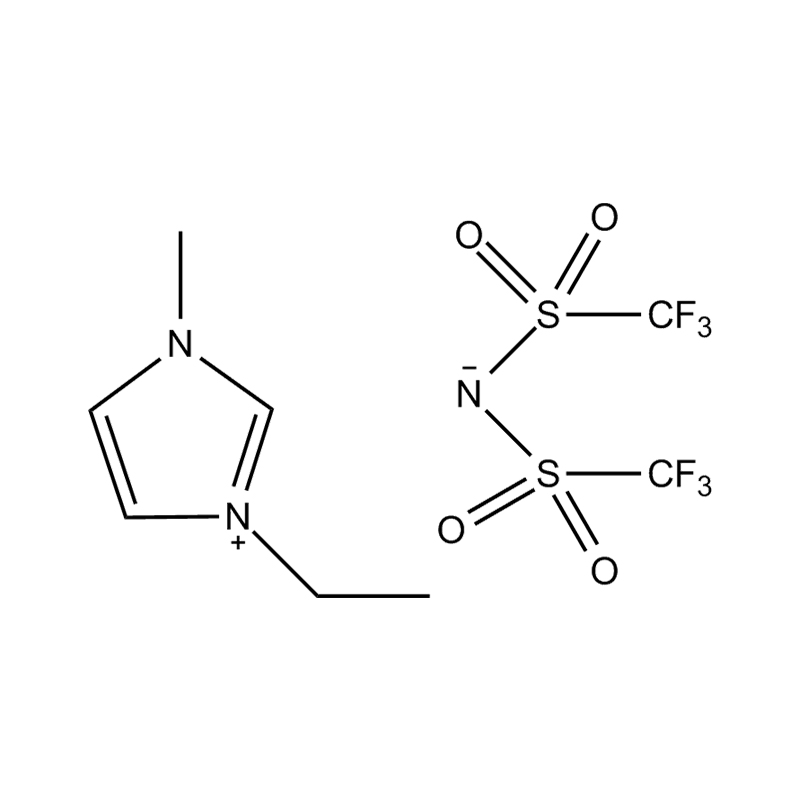

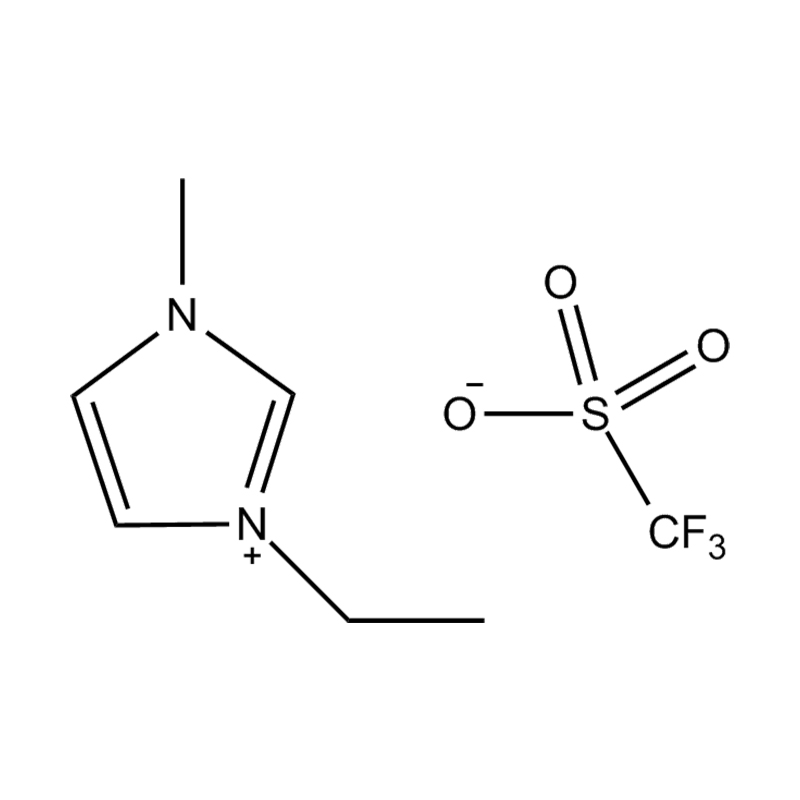

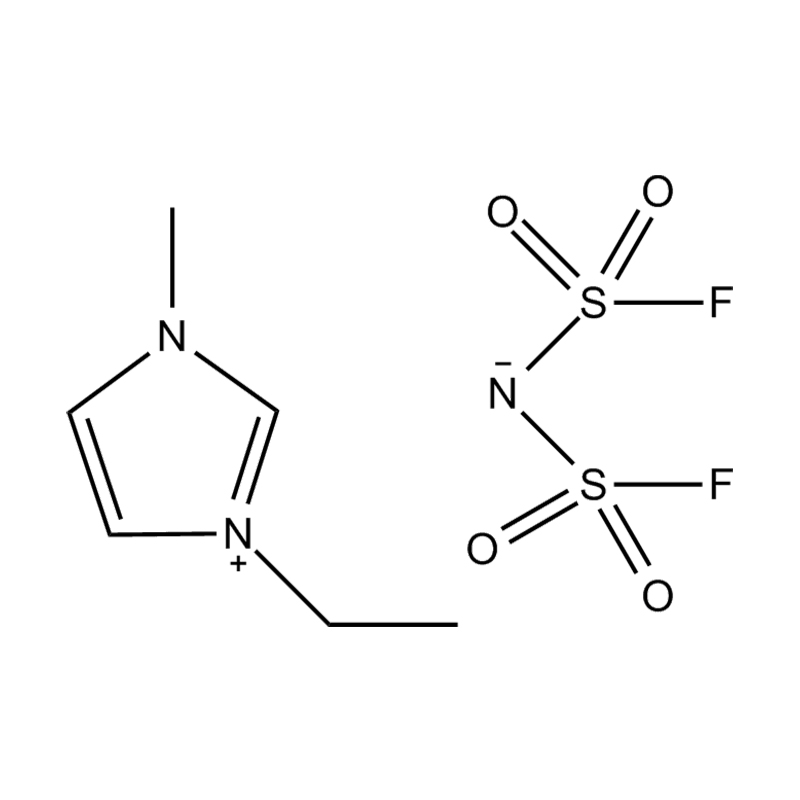

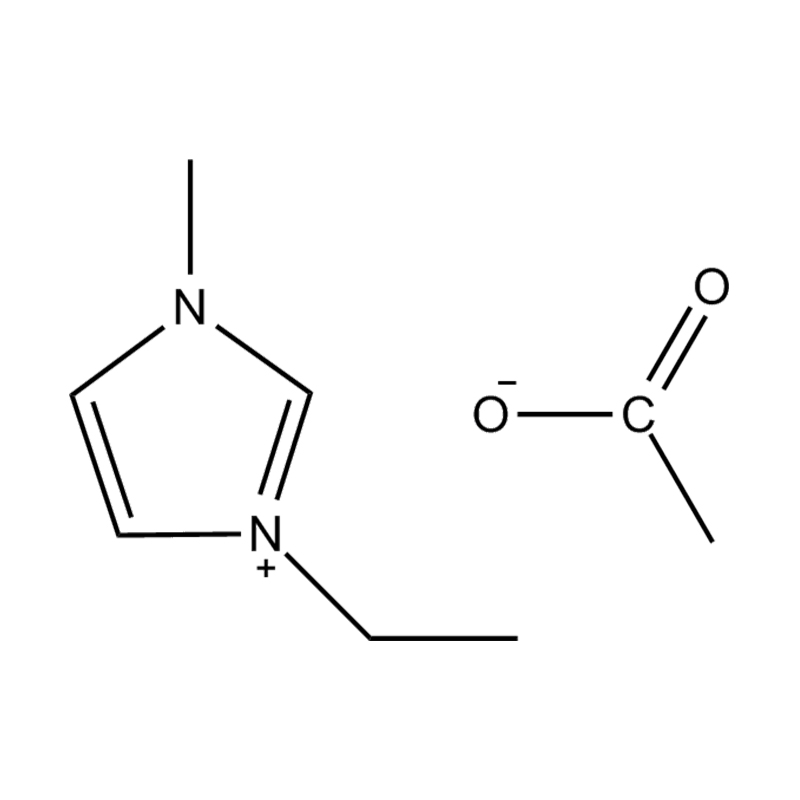

Ionic Liquid Catalysts

Ionic liquids are salts that remain liquid at relatively low temperatures and can act as both solvents and catalysts for PET degradation. These compounds can dissolve PET at moderate temperatures, bringing the polymer chains into intimate contact with nucleophilic reagents. Basic ionic liquids containing imidazolium, pyridinium, or phosphonium cations paired with acetate, hydroxide, or amino acid anions have demonstrated effective PET depolymerization. The advantages of ionic liquids include tunable properties through structural modification, low volatility, and recyclability. However, their high cost and potential environmental impacts remain challenges that researchers are addressing through the development of bio-based and less toxic ionic liquid variants.

Solid Acid and Base Catalysts

Solid acid and base catalysts offer advantages in terms of easy separation, recyclability, and reduced corrosion compared to their liquid counterparts. Solid acids such as sulfated zirconia, zeolites, and functionalized silica can catalyze PET methanolysis or glycolysis through Lewis or Brønsted acid sites. Solid bases including metal oxides (calcium oxide, magnesium oxide), hydrotalcites, and basic zeolites promote ester bond cleavage through activation of nucleophilic reagents. These heterogeneous catalysts can be recovered by simple filtration or centrifugation and reused multiple times with minimal loss of activity. Recent innovations include the development of bifunctional catalysts containing both acidic and basic sites, which synergistically enhance PET degradation rates by simultaneously activating both the polymer and the degrading reagent.

Mechanisms of Catalytic PET Degradation

Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which catalysts break down PET is crucial for optimizing degradation processes and developing more efficient catalytic systems. Different catalysts employ distinct mechanisms, though most involve the cleavage of ester bonds through nucleophilic substitution reactions. The rate and selectivity of these reactions depend on factors including catalyst structure, reaction conditions, PET crystallinity, and the presence of additives or contaminants.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis Mechanism

Enzymatic hydrolysis of PET proceeds through a multi-step mechanism involving substrate binding, acyl-enzyme intermediate formation, and product release. The enzyme's active site recognizes and binds to the PET surface, with aromatic residues in the binding pocket interacting with the terephthalate groups through π-π stacking interactions. The catalytic serine performs a nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl carbon of the ester bond, forming a tetrahedral intermediate stabilized by the oxyanion hole. This intermediate collapses to form an acyl-enzyme intermediate with release of one product molecule. Water then attacks the acyl-enzyme intermediate, regenerating the free enzyme and releasing the carboxylic acid product. The rate-limiting step is often the initial substrate binding or the acylation step, depending on the enzyme variant and reaction conditions. Enzyme engineering efforts focus on improving these steps through mutations that enhance substrate affinity, increase active site flexibility, or stabilize transition states.

Chemical Glycolysis Mechanism

Glycolysis involves the transesterification of PET with excess glycol (typically ethylene glycol or diethylene glycol) in the presence of a catalyst. The catalyst activates the carbonyl group of the ester through coordination or protonation, making it more electrophilic. Simultaneously, the glycol is activated through deprotonation, enhancing its nucleophilicity. The activated glycol attacks the carbonyl carbon, forming a tetrahedral intermediate that collapses to cleave the ester bond and form a new ester linkage with the glycol. Repeated cleavage reactions progressively reduce the polymer molecular weight, ultimately yielding bis(hydroxyethyl) terephthalate (BHET) as the primary product. The reaction kinetics follow a pattern of rapid initial depolymerization as accessible amorphous regions are attacked, followed by slower degradation of crystalline domains as they gradually become accessible through swelling and surface erosion.

Methanolysis and Aminolysis Pathways

Methanolysis proceeds through a similar transesterification mechanism to glycolysis but uses methanol as the nucleophile, yielding dimethyl terephthalate (DMT) and ethylene glycol as products. This reaction typically requires higher temperatures and pressures than glycolysis due to methanol's lower boiling point and reduced nucleophilicity. Aminolysis employs amines as nucleophiles, resulting in the formation of terephthalamides and ethylene glycol. Primary and secondary amines show different reactivities, with primary amines generally being more reactive but producing less soluble products. These alternative degradation pathways can be advantageous when specific products are desired or when dealing with particular waste streams, though they may require more sophisticated catalyst systems to achieve acceptable conversion rates and selectivities.

Factors Affecting Catalyst Performance

The effectiveness of PET degradation catalysts depends on numerous interrelated factors that influence reaction kinetics, product distribution, and overall process economics. Optimizing these parameters is essential for developing commercially viable recycling technologies. Understanding how each factor affects catalyst performance allows for rational process design and troubleshooting of operational challenges in industrial applications.

- Temperature plays a critical role in PET degradation, affecting both catalyst activity and polymer accessibility. For enzymatic catalysts, temperature must be balanced between increasing reaction rates and maintaining protein stability, with most enzymes showing optimal activity between 40-70°C. Chemical catalysts typically operate at higher temperatures of 180-250°C, where PET becomes more amorphous and accessible. Temperature also influences product distribution, with higher temperatures favoring complete depolymerization to monomers over oligomer formation.

- PET crystallinity significantly impacts degradation rates, as amorphous regions are far more accessible to catalysts than crystalline domains. Virgin PET bottles typically contain 30-40% crystalline material, which is largely resistant to enzymatic attack. Pretreatments such as mechanical grinding, thermal treatment near the glass transition temperature, or solvent swelling can reduce crystallinity and expose more polymer surface area. Some processes intentionally operate at temperatures above the glass transition temperature (67-81°C) to maintain the polymer in a more accessible state during degradation.

- Particle size and surface area directly affect degradation kinetics, as catalytic reactions occur at the polymer surface. Smaller particle sizes provide more surface area for catalyst interaction, accelerating degradation. Industrial processes typically grind PET waste into flakes of 5-10 mm, though finer grinding to sub-millimeter particles can further enhance rates. However, extremely fine particles can cause handling difficulties and agglomeration issues that must be managed through appropriate reactor design and agitation.

- Catalyst concentration and substrate loading must be optimized to maximize economic efficiency while achieving desired conversion rates. Higher catalyst concentrations generally increase reaction rates but also increase costs and potential product contamination. Substrate loading affects mass transfer, with very high PET concentrations potentially limiting reagent access to polymer surfaces. Typical enzymatic processes use enzyme concentrations of 0.1-5 mg per gram of PET, while chemical processes may use catalyst concentrations of 0.5-5% by weight relative to PET.

- pH and reaction medium composition influence catalyst stability and activity, particularly for enzymes. Most PET-degrading enzymes show optimal activity in neutral to slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7-9). The reaction medium's ionic strength, buffer composition, and presence of surfactants or cosolvents can all affect enzyme-substrate interactions and overall performance. For chemical catalysts, solvent polarity and acidity/basicity can dramatically influence reaction rates and pathways.

Applications in PET Recycling and Waste Management

PET degradation catalysts are being implemented in various recycling and waste management applications, from industrial-scale chemical recycling facilities to bioremediation of environmental plastic pollution. These applications address different segments of the plastic waste problem and offer complementary approaches to traditional mechanical recycling. The choice of catalyst system depends on the specific waste stream characteristics, desired products, economic constraints, and environmental considerations.

Industrial Chemical Recycling

Large-scale chemical recycling facilities use catalysts to depolymerize post-consumer PET into monomers or oligomers that can be purified and repolymerized into virgin-quality PET. This approach enables true circular recycling, unlike mechanical recycling which leads to progressive material degradation. Companies like Loop Industries, Carbios, and Ioniqa Technologies have developed proprietary catalytic processes operating at commercial or near-commercial scales. These facilities can process mixed-color PET waste, contaminated materials, and even polyester textiles that are unsuitable for mechanical recycling. The recovered monomers meet the same purity standards as petroleum-derived materials, allowing them to be used in food-contact applications and high-performance fibers without quality compromises.

Enzymatic Biorecycling Systems

Enzymatic biorecycling represents an emerging application that promises lower energy consumption and reduced environmental impact compared to thermochemical processes. Carbios has pioneered a commercial-scale enzymatic PET recycling process that operates at 65°C and achieves over 90% conversion of PET to monomers within 10-16 hours. The process uses engineered enzyme variants with enhanced thermal stability and activity, deployed in large bioreactors where ground PET waste is mixed with enzyme solution under controlled conditions. After degradation, the monomers are separated from the enzyme through filtration or precipitation, purified through crystallization or distillation, and sold for repolymerization. The enzyme can potentially be recovered and reused, further improving process economics. Pilot facilities are also exploring the integration of enzyme production with the recycling process, using fermentation systems to produce fresh enzyme on-site.

Treatment of Microplastic Pollution

Catalytic degradation technologies are being investigated for addressing microplastic pollution in aquatic environments and wastewater treatment systems. Immobilized enzymes on solid supports or encapsulated in semi-permeable membranes can be deployed in bioreactors to treat contaminated water streams. Advanced oxidation processes using photocatalytic materials like titanium dioxide or zinc oxide generate reactive oxygen species that break down PET microplastics into smaller molecules, though complete mineralization remains challenging. Research is also exploring the use of microbial consortia containing PET-degrading organisms in bioremediation applications, where the microbes are introduced into contaminated sites to gradually degrade plastic accumulations. While still largely at the research stage, these approaches offer potential solutions for environmental plastic pollution that cannot be addressed through conventional waste collection and recycling.

Comparison of Catalyst Types

Different PET degradation catalysts offer distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different applications and contexts. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for selecting the most appropriate technology for specific recycling scenarios. The following comparison highlights key performance metrics and practical considerations across the main catalyst categories.

| Catalyst Type | Operating Temperature | Reaction Time | Energy Efficiency | Product Purity | Environmental Impact |

| Enzymatic (PETase) | 40-70°C | 10-24 hours | High | Very High | Very Low |

| Metal-Based (Zinc acetate) | 180-240°C | 2-6 hours | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Ionic Liquids | 120-180°C | 1-4 hours | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Solid Acid/Base | 180-220°C | 3-8 hours | Moderate | High | Low-Moderate |

| Alkali Hydrolysis | 200-250°C | 1-3 hours | Low | Moderate | High |

Recent Innovations and Breakthrough Technologies

The field of catalytic PET degradation is experiencing rapid innovation, with new catalyst designs, process configurations, and hybrid approaches emerging from academic research and industrial development programs. These advances are progressively improving the economic viability and environmental sustainability of chemical recycling, bringing it closer to widespread commercial implementation. Recent breakthroughs have addressed key bottlenecks in catalyst performance, stability, and scalability.

Thermophilic and Mesophilic Enzyme Engineering

Researchers have developed enhanced PETase variants through directed evolution and rational design that exhibit dramatically improved performance. Recent enzymes can operate at temperatures up to 85°C, well above PET's glass transition temperature, while maintaining stability for extended periods. These thermophilic enzymes achieve degradation rates 10-100 times faster than early PETase variants. Computational modeling and machine learning approaches are accelerating enzyme engineering by predicting beneficial mutations before experimental testing. Some variants incorporate multiple beneficial mutations that synergistically enhance substrate binding, catalytic turnover, and thermal stability. Fusion enzymes linking PETase and MHETase domains have been created to streamline the degradation pathway, eliminating the need for separate enzyme additions and reducing intermediate accumulation.

Nanomaterial-Based Catalysts

Nanostructured catalysts incorporating metal nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks, and nanocomposite materials offer enhanced catalytic performance through increased surface area and unique quantum effects. Gold, silver, and platinum nanoparticles supported on various oxide carriers show photocatalytic activity for PET degradation under UV or visible light irradiation. Carbon-based nanomaterials such as graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes functionalized with catalytic sites provide excellent mass transfer properties and mechanical strength. Core-shell nanoparticles with catalytically active shells and magnetically responsive cores enable easy catalyst recovery through magnetic separation, addressing a key challenge in heterogeneous catalysis. These advanced nanomaterials are being integrated into continuous-flow reactors and membrane systems for efficient processing of PET waste streams.

Hybrid and Cascade Catalytic Systems

Innovative approaches are combining multiple catalyst types in sequential or simultaneous reaction schemes to leverage their complementary strengths. Enzymatic pretreatment followed by chemical catalysis can efficiently process highly crystalline PET by first using enzymes to create surface defects and reduce polymer molecular weight, then applying chemical catalysts for rapid complete depolymerization. Photocatalytic systems using semiconductors like titanium dioxide or cadmium sulfide generate reactive species that both degrade PET directly and activate chemical co-catalysts. Bifunctional catalysts containing both metal centers and acidic or basic sites show synergistic effects in PET glycolysis, with each site contributing to different mechanistic steps. These hybrid systems aim to achieve the environmental benefits of enzymatic catalysis with the speed and robustness of chemical methods.

Economic and Environmental Considerations

The commercial viability and environmental sustainability of catalytic PET degradation depend on multiple economic and ecological factors beyond just technical performance. Life cycle assessments, techno-economic analyses, and market considerations all play crucial roles in determining whether a particular catalyst system can compete with virgin PET production and mechanical recycling. Understanding these broader implications helps guide technology development toward solutions that are both economically competitive and genuinely beneficial for environmental sustainability.

Process Economics and Cost Analysis

The economic competitiveness of catalytic PET recycling depends primarily on catalyst cost, energy consumption, product yields, and capital investment requirements. Enzymatic processes typically have higher catalyst costs due to enzyme production expenses, though this is offset by lower energy requirements and milder operating conditions that reduce equipment costs. Chemical processes using inexpensive metal salts have lower catalyst costs but require more energy-intensive operations and more robust equipment to handle high temperatures and pressures. Techno-economic models suggest that catalytic recycling can achieve costs of $800-1200 per ton of recovered monomers, comparable to or lower than virgin PET production costs ($1000-1400 per ton) depending on crude oil prices. Process integration, catalyst recycling, and economies of scale in large facilities can significantly improve economics, potentially achieving costs below $700 per ton at scales exceeding 50,000 tons per year.

Life Cycle Environmental Impact

Life cycle assessments comparing catalytic recycling to virgin production and mechanical recycling reveal significant environmental benefits. Enzymatic PET degradation reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 30-50% compared to virgin PET production from petroleum, primarily due to avoided oil extraction and refining. Chemical catalytic processes show emission reductions of 15-35%, with the benefit varying based on energy sources and process efficiency. Water consumption, toxicity impacts, and eutrophication potential also tend to be lower for catalytic recycling, though careful management of chemical inputs and waste streams is essential. The ability to recycle contaminated and mixed-color PET that would otherwise be incinerated or landfilled provides additional environmental benefits by diverting waste from disposal. However, catalytic recycling currently requires more energy than mechanical recycling, making it most appropriate for materials unsuitable for mechanical processing rather than as a universal replacement.

Market and Regulatory Factors

Regulatory frameworks and market dynamics significantly influence the adoption of catalytic PET recycling technologies. Extended producer responsibility legislation in Europe and other regions is creating stronger economic incentives for using recycled content in packaging. Some jurisdictions are implementing minimum recycled content requirements or taxes on virgin plastic use that improve the competitiveness of recycling technologies. Brand commitments from major companies like Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Nestlé to incorporate significant recycled content in their packaging are driving demand for high-quality recycled PET. The food safety approval process for recycled PET used in food contact applications creates regulatory barriers that favor advanced recycling methods producing truly virgin-quality monomers over mechanically recycled materials. Carbon pricing mechanisms and renewable energy incentives can further improve the economics of catalytic recycling, particularly for energy-efficient enzymatic processes powered by renewable electricity.

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite significant progress in catalyst development, several practical challenges must be addressed to achieve widespread commercial deployment of catalytic PET recycling. These challenges span technical, operational, and systemic issues that affect process reliability, product quality, and overall economics. Understanding these obstacles and the strategies being developed to overcome them is essential for realistic assessment of technology readiness and commercial timelines.

- Handling mixed and contaminated waste streams remains a significant challenge, as real-world PET waste contains various contaminants including labels, adhesives, food residues, pigments, and other polymers. Pre-sorting and washing can remove some contaminants but add cost and complexity. Robust catalysts that tolerate common contaminants or process designs that segregate different waste qualities are being developed to address this issue. Some enzymatic processes show surprising tolerance to contaminants, maintaining activity even with colored PET or moderate organic contamination.

- Enzyme production costs and stability limitations constrain the economics of biocatalytic approaches. Current enzyme production relies on fermentation in specialized microbial hosts, with downstream purification adding significant cost. Cell-free enzyme production systems, improved expression hosts, and strategies for enzyme immobilization and reuse are being investigated to reduce enzyme costs. Engineered enzyme variants with extended operational lifetimes allow lower enzyme loadings and multiple use cycles, dramatically improving process economics.

- Scaling from laboratory to industrial scales introduces challenges related to mass transfer, heat management, and equipment design. Small-scale experiments may not accurately predict performance in large reactors where mixing, heating, and catalyst distribution differ significantly. Pilot plant operations are essential for validating process designs and identifying unexpected issues before commercial implementation. Companies developing catalytic recycling technologies typically operate demonstration facilities processing tens to hundreds of tons per year before committing to commercial-scale plants.

- Product purification and quality control require careful attention to meet specifications for repolymerization. Residual catalyst, degradation byproducts, and impurities from the waste stream can affect the properties of repolymerized PET if not adequately removed. Crystallization, distillation, filtration, and adsorption processes are employed to purify recovered monomers. Quality assurance testing protocols verify that recycled monomers meet the same standards as virgin materials for critical applications.

- Integration with existing waste management infrastructure and supply chains is necessary for consistent feedstock supply and product distribution. Partnerships with waste collectors, sorters, and PET producers help ensure reliable material flows. Some companies are establishing collection networks specifically for their recycling operations, while others work with existing recyclers to source pre-sorted PET waste. Logistics optimization and feedstock contracts help stabilize operations and reduce material cost volatility.

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The field of catalytic PET degradation continues to evolve rapidly, with numerous promising research directions that could further improve performance, reduce costs, and expand applications. Emerging technologies at early stages of development may lead to breakthrough capabilities that transform plastic recycling. Identifying and pursuing high-impact research opportunities will accelerate the transition to circular plastic economies and more sustainable materials management systems.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications are revolutionizing catalyst discovery and optimization. Computational models trained on existing enzyme or catalyst data can predict promising modifications or entirely novel catalytic structures. High-throughput screening platforms combined with automated testing enable rapid evaluation of thousands of catalyst variants. These approaches are dramatically accelerating the pace of catalyst development, potentially reducing the time from initial discovery to optimized industrial catalyst from years to months. Integration of process simulation models with catalyst performance data allows simultaneous optimization of both catalyst properties and operating conditions.

Development of catalysts capable of degrading multiple plastic types or mixed plastic waste would significantly expand the applicability of chemical recycling. Most current catalysts are specific to PET, requiring pure feedstocks or extensive sorting. Catalysts with broader substrate specificity could process mixed polyester waste or even handle combinations of different polymer types. This capability would be particularly valuable for textile recycling, where blended fabrics containing PET, cotton, and other fibers are common. Research into catalytic systems that can selectively depolymerize target polymers while leaving others intact offers another approach to handling mixed waste streams.

In-situ and continuous processing technologies promise to improve productivity and reduce costs compared to batch operations. Continuous-flow reactors with immobilized enzymes or packed-bed catalytic reactors enable steady-state operation with high throughput. Membrane reactors that separate products as they form can shift reaction equilibria and prevent product inhibition, accelerating degradation. Integration of degradation with product purification and repolymerization in continuous process trains would minimize intermediate storage and handling. These advanced process configurations are moving from laboratory concepts toward pilot demonstration, with commercial implementation expected in coming years.

Exploration of alternative products and value-added applications for PET degradation products could improve process economics and create new markets. While recovering monomers for repolymerization is the primary goal, degradation intermediates and modified products may have value in other applications. Oligomers from partial degradation can serve as reactive intermediates for polyurethanes, epoxy resins, or alkyd coatings. Functionalized terephthalic acid derivatives could be used in specialty chemicals or pharmaceutical synthesis. Identifying and developing these alternative product pathways provides additional revenue streams and increases the flexibility of recycling operations to respond to market conditions.

English

English Deutsch

Deutsch Español

Español 中文简体

中文简体