Content

- 1 What Are Solid Electrolytes and Why Do They Matter?

- 2 Oxide-Based Solid Electrolytes

- 3 Sulfide-Based Solid Electrolytes

- 4 Polymer-Based Solid Electrolytes

- 5 Halide-Based Solid Electrolytes

- 6 Side-by-Side Comparison of the Four Types

- 7 Critical Challenges Shared Across All Four Types

- 8 Hybrid and Composite Electrolyte Strategies

- 9 Which Solid Electrolyte Is Right for Your Application?

What Are Solid Electrolytes and Why Do They Matter?

Solid electrolytes are the defining component of solid-state batteries, replacing the liquid or gel electrolytes found in conventional lithium-ion cells. In a traditional battery, the electrolyte is a flammable organic solvent that allows lithium ions to shuttle between the anode and cathode. This liquid phase introduces risks of leakage, thermal runaway, and electrochemical degradation over time. Solid electrolytes eliminate these vulnerabilities by providing an ionically conductive, mechanically stable, and non-flammable medium through which lithium ions can travel.

The performance of a solid-state battery is, in large part, determined by the type of solid electrolyte used. Key metrics include ionic conductivity (measured in S/cm), electrochemical stability window, chemical compatibility with electrode materials, mechanical flexibility, and ease of manufacturing. No single material perfectly satisfies all these criteria, which is why researchers and manufacturers explore four distinct categories of solid electrolytes: oxide-based, sulfide-based, polymer-based, and halide-based. Each type brings a unique combination of strengths and trade-offs that make it suitable for different applications and form factors.

Oxide-Based Solid Electrolytes

Oxide-based solid electrolytes are among the most extensively studied materials in solid-state battery research. They are broadly categorized into crystalline ceramics and amorphous glass-ceramics, and they are prized for their exceptional chemical stability, wide electrochemical windows, and resistance to moisture and air. However, their inherently rigid and brittle nature creates challenges for scalable manufacturing and solid-solid interfacial contact with electrodes.

Garnet-Type: LLZO

Lithium lanthanum zirconium oxide (Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂), commonly known as LLZO, is one of the most prominent garnet-type oxide electrolytes. It exhibits an ionic conductivity of approximately 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻³ S/cm at room temperature in its cubic phase, which is orders of magnitude higher than the tetragonal phase. Stabilizing the cubic phase requires doping with elements such as aluminum, tantalum, or niobium. LLZO is chemically stable against metallic lithium anodes, making it a strong candidate for lithium-metal battery architectures. Its main drawbacks include high sintering temperatures (above 1000°C), grain boundary resistance, and poor wettability with lithium metal due to surface contamination by Li₂CO₃.

NASICON-Type and Perovskite-Type

NASICON-type electrolytes, such as LAGP (Li₁.₅Al₀.₅Ge₁.₅(PO₄)₃) and LATP (Li₁.₃Al₀.₃Ti₁.₇(PO₄)₃), offer high ionic conductivity and excellent atmospheric stability. LAGP reaches conductivity values up to 5 × 10⁻⁴ S/cm. However, LATP suffers from reduction of Ti⁴⁺ when in direct contact with lithium metal. Perovskite-type electrolytes like LLTO (Li₃ₓLa₂/₃₋ₓTiO₃) demonstrate high bulk conductivity (~10⁻³ S/cm) but suffer from very high grain boundary resistance and chemical incompatibility with lithium anodes due to Ti reduction, limiting practical deployment.

LIPON (Lithium Phosphorus Oxynitride)

LIPON is an amorphous thin-film electrolyte deposited via radio-frequency magnetron sputtering. Although its ionic conductivity is relatively modest (~2 × 10⁻⁶ S/cm), LIPON excels in ultra-thin film applications (< 1 μm thick), which compensates for the low conductivity. It is chemically stable with lithium metal and has a wide electrochemical window exceeding 5 V. LIPON is the electrolyte of choice in thin-film microbatteries used in implantable medical devices, smart cards, and MEMS sensors.

Sulfide-Based Solid Electrolytes

Sulfide-based solid electrolytes currently hold the record for room-temperature ionic conductivity among solid-state materials, with some compositions rivaling or exceeding that of conventional liquid electrolytes (~10⁻² S/cm). Their soft mechanical nature allows cold-pressing into dense pellets without sintering, which dramatically simplifies cell manufacturing. These properties have made sulfide electrolytes the leading candidate for automotive-grade solid-state batteries.

Argyrodite: Li₆PS₅Cl

Li₆PS₅Cl belongs to the argyrodite crystal structure family and achieves ionic conductivity in the range of 10⁻³ to 10⁻² S/cm. It can be synthesized via mechanochemical ball milling followed by annealing, making it compatible with scalable production. Li₆PS₅Cl is compatible with sulfide-based cathodes and can be incorporated into composite cathode layers. Its primary weaknesses include narrow electrochemical stability against high-voltage cathodes and instability in ambient air — it reacts with moisture to produce toxic hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) gas, necessitating dry-room manufacturing environments.

Thio-LISICON and LGPS

Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂ (LGPS), first reported by Kanno et al. in 2011, was a landmark discovery — it demonstrated an ionic conductivity of 12 × 10⁻³ S/cm, comparable to liquid electrolytes. LGPS belongs to the thio-LISICON structural family and owes its exceptional conductivity to a three-dimensional lithium diffusion pathway. However, LGPS contains germanium, a costly element, and is unstable against both lithium metal anodes and high-voltage cathode materials (>3 V vs. Li⁺/Li). Partial substitution of germanium with silicon (Li₁₀SiP₂S₁₂) offers a more cost-effective variant with slightly lower but still impressive conductivity (~8 × 10⁻³ S/cm).

Glass-Ceramic Sulfides: Li₂S-P₂S₅

The binary system Li₂S-P₂S₅ produces glassy or glass-ceramic sulfide electrolytes, the most notable being β-Li₃PS₄ and Li₇P₃S₁₁. These materials offer moderate ionic conductivity (~10⁻⁴ S/cm for β-Li₃PS₄ and up to 3.2 × 10⁻³ S/cm for Li₇P₃S₁₁) and are more cost-effective than LGPS due to the absence of rare elements. Glass-ceramic processing enables control over crystallite size and phase distribution, further tuning conductivity and mechanical properties. They remain moisture-sensitive and require handling in inert atmospheres.

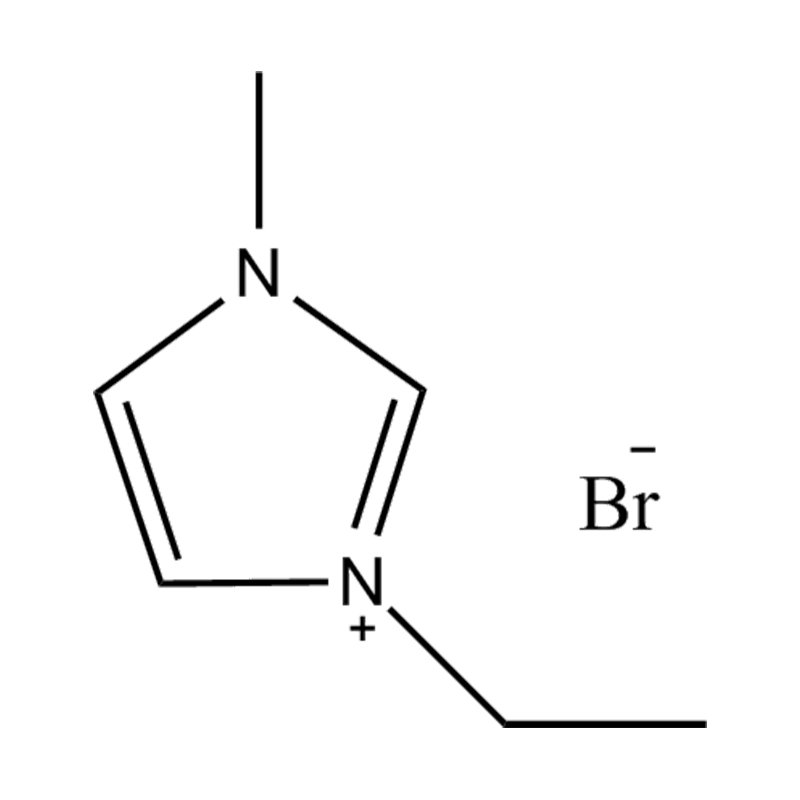

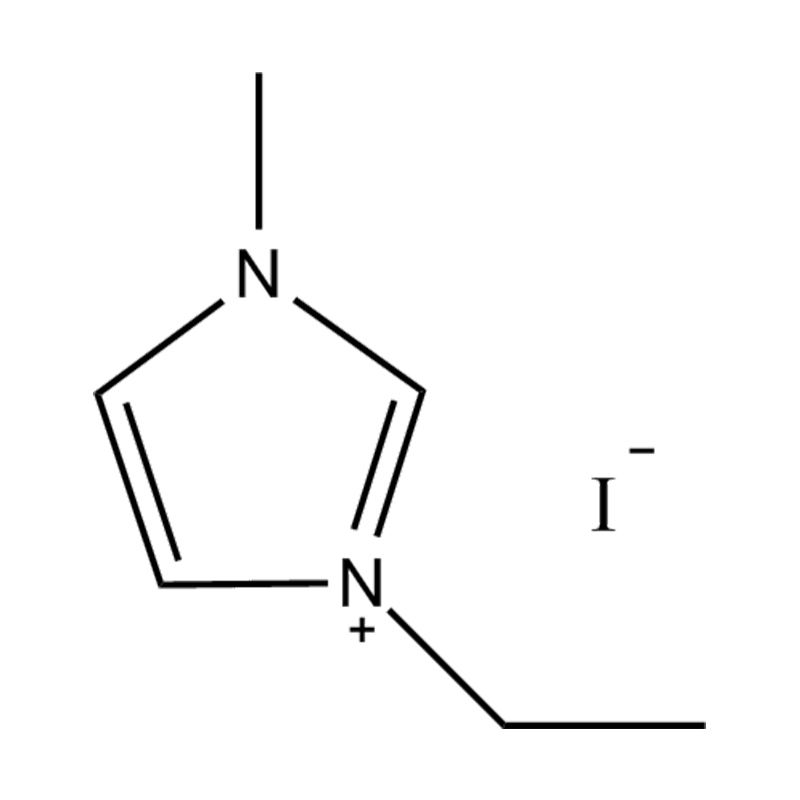

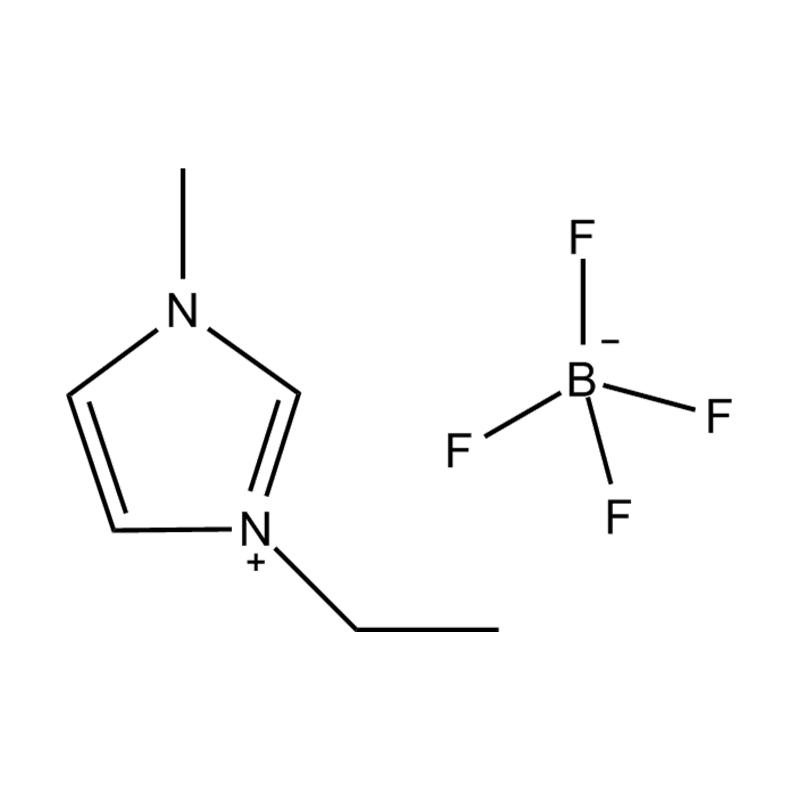

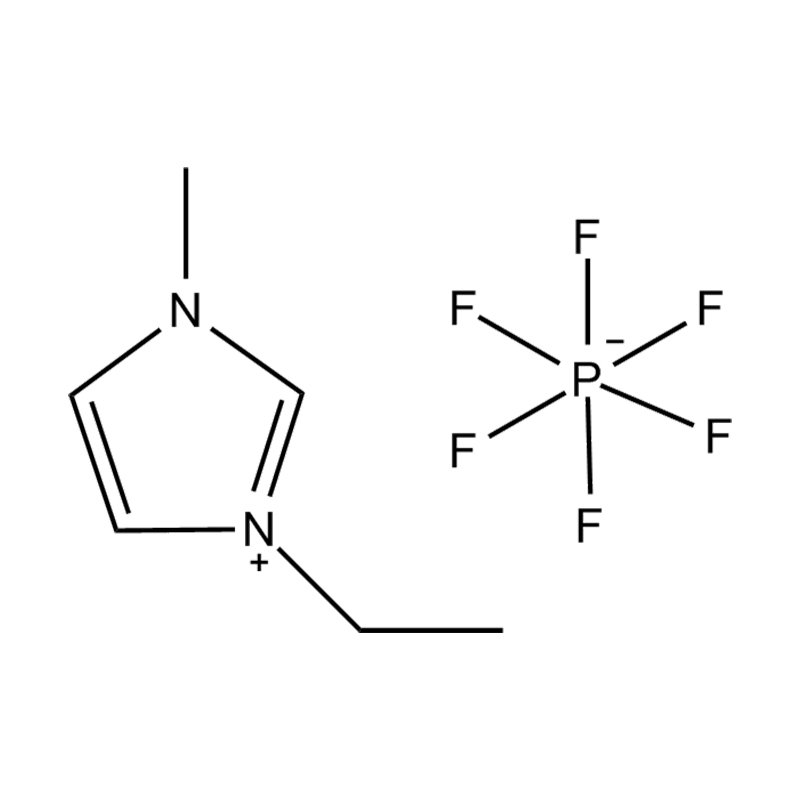

Polymer-Based Solid Electrolytes

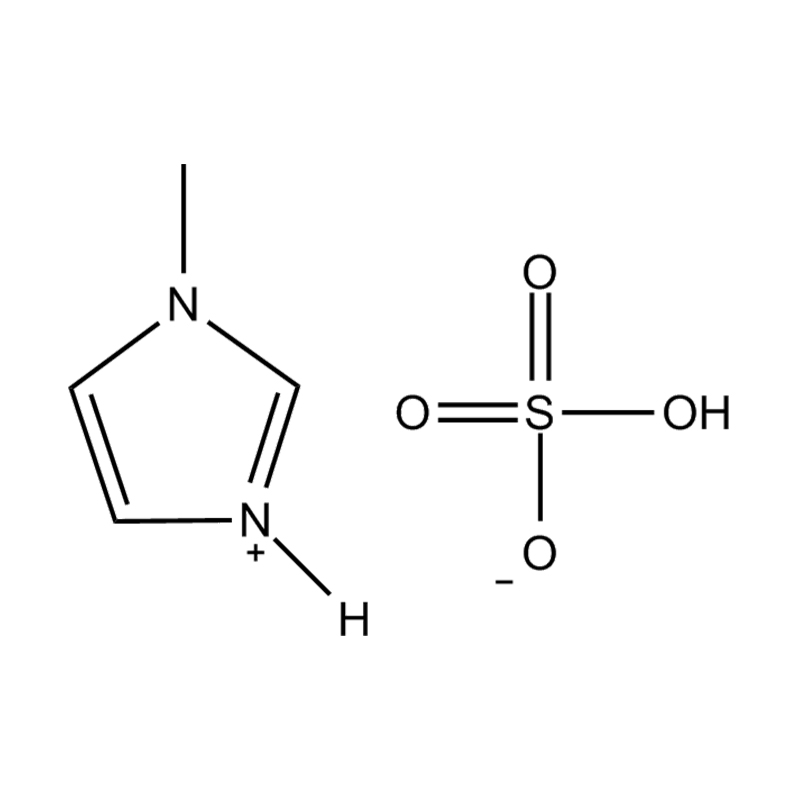

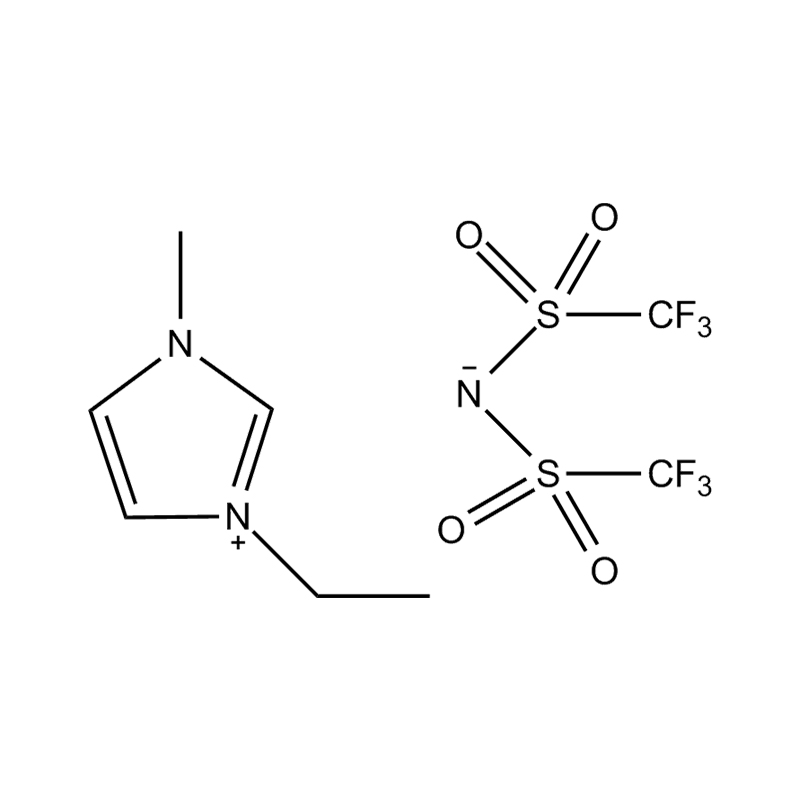

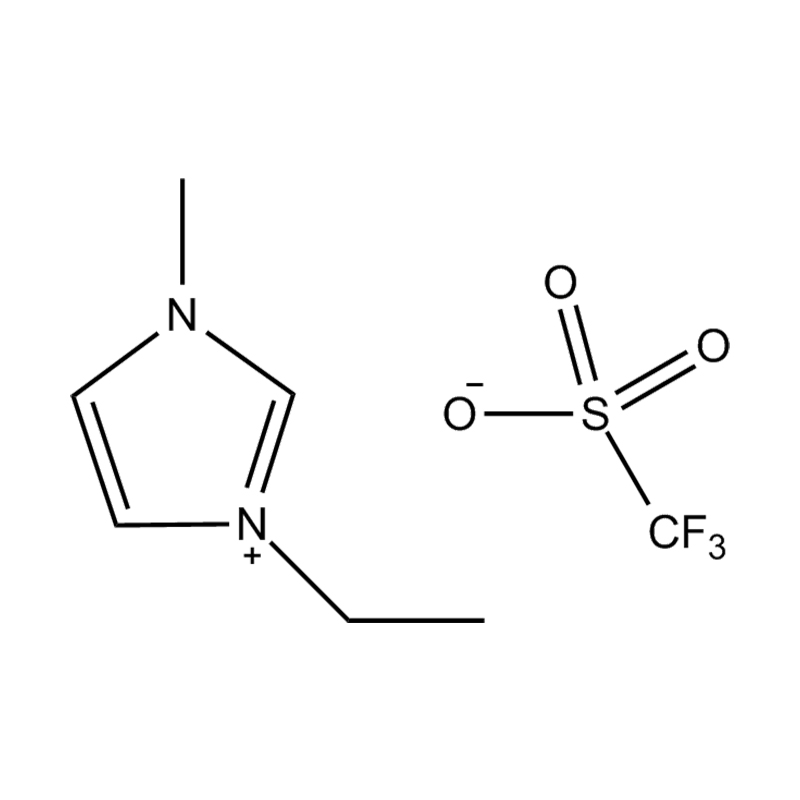

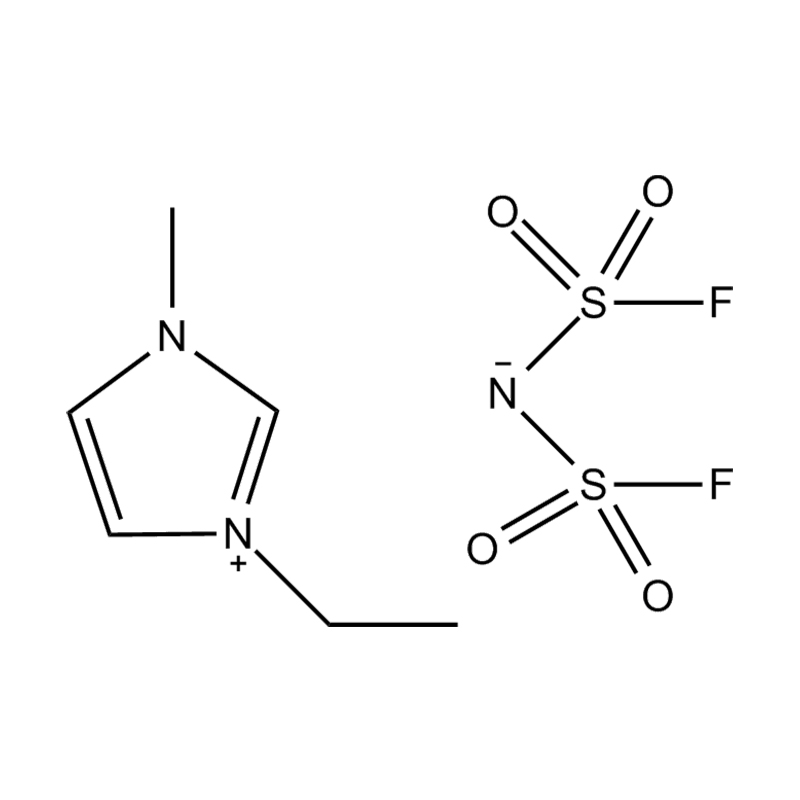

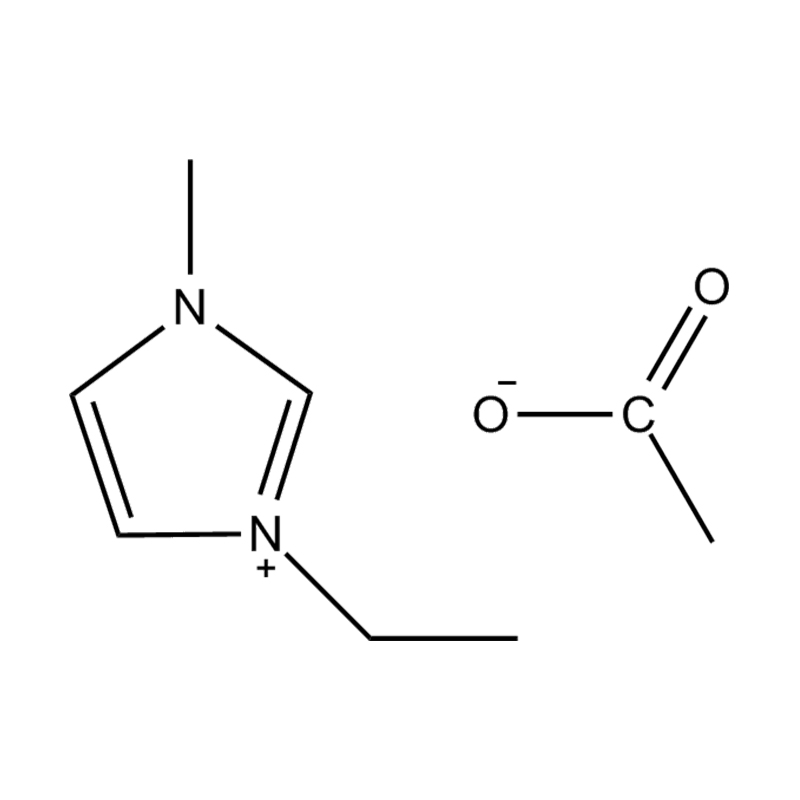

Polymer-based solid electrolytes offer a fundamentally different approach: instead of ceramic or glass conductors, they use flexible polymer matrices doped with lithium salts to create ion transport pathways. Their inherent mechanical flexibility allows roll-to-roll processing using existing lithium-ion battery manufacturing equipment, offering a potentially low-cost and scalable route to solid-state cells. The trade-off is that most pure polymer electrolytes require elevated operating temperatures to achieve acceptable ionic conductivity.

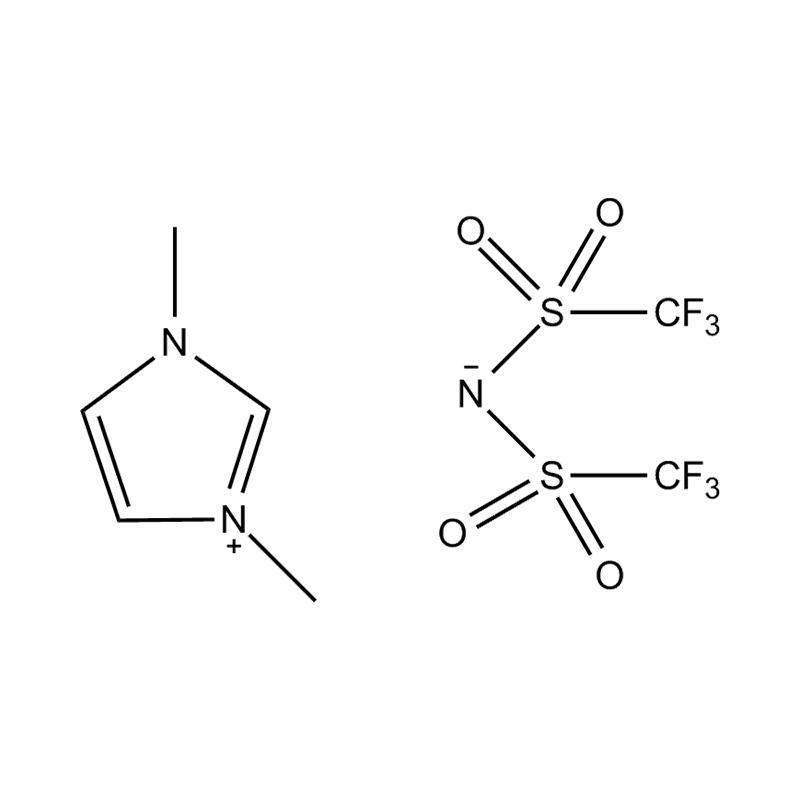

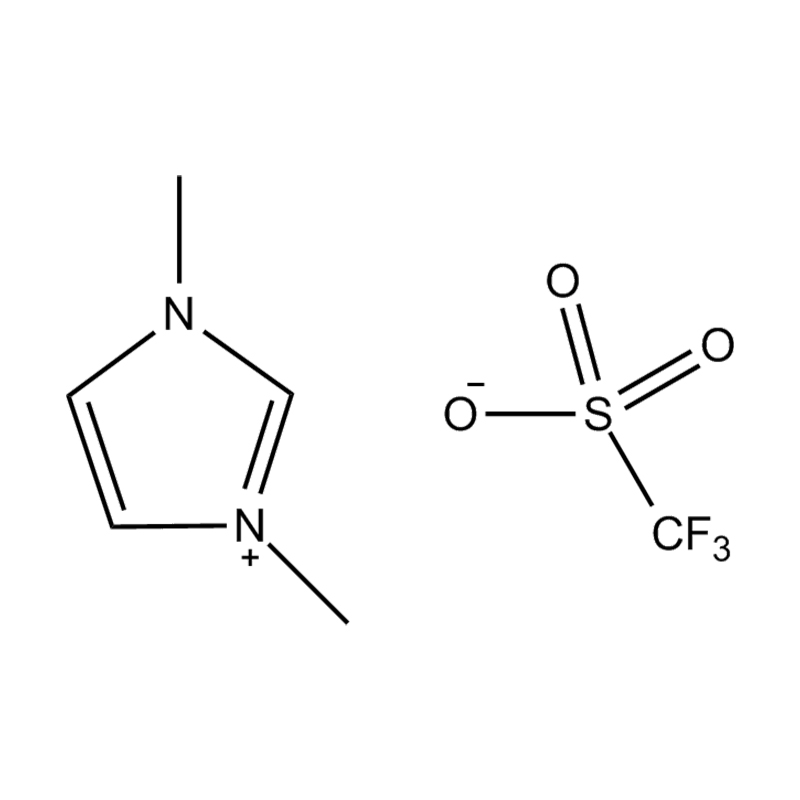

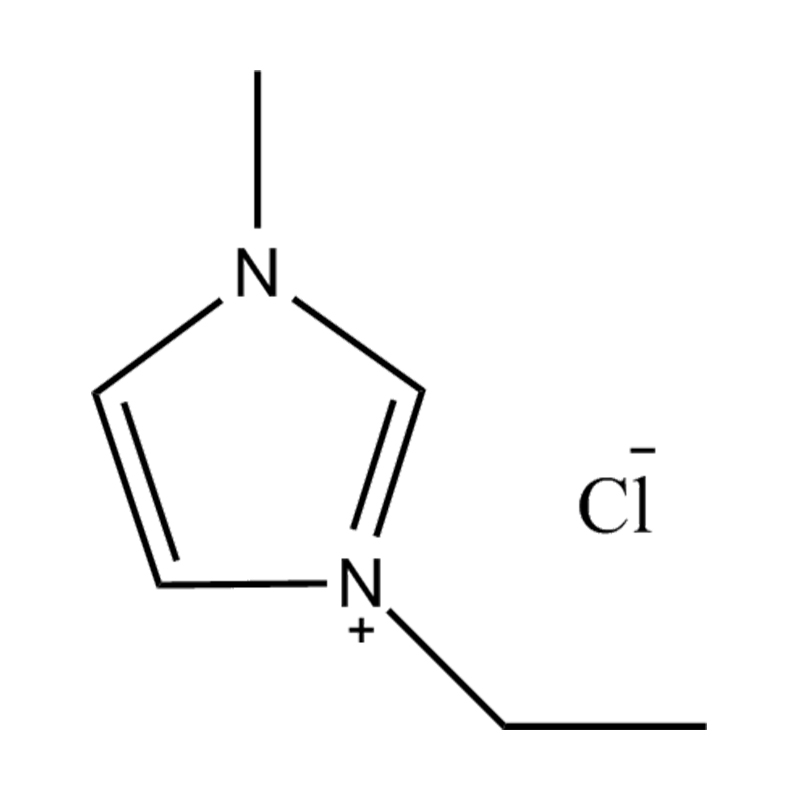

Polyethylene Oxide (PEO)-Based Systems

PEO is the most commercially mature polymer electrolyte material. It complexes lithium salts such as LiTFSI (lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide) through its ether oxygen segments, which coordinate with Li⁺ ions. Ion transport in PEO occurs through segmental polymer chain motion in the amorphous phase. At temperatures above 60°C, PEO-LiTFSI achieves conductivity of ~10⁻³ S/cm. Bolloré's BlueSolutions has commercialized PEO-based solid-state batteries for electric buses and grid storage operating at 60–80°C. Below this range, the semi-crystalline nature of PEO reduces conductivity to unacceptably low values (~10⁻⁷ S/cm at room temperature), limiting its use in ambient-temperature consumer electronics.

Composite and Gel Polymer Electrolytes

To overcome the room-temperature conductivity limitation of PEO, researchers have developed composite polymer electrolytes (CPEs) by incorporating inorganic fillers — such as LLZO nanoparticles, TiO₂, or Al₂O₃ — into the polymer matrix. These fillers disrupt PEO crystallinity, increase the fraction of amorphous phase, and create additional ion transport pathways along filler-polymer interfaces. CPEs have achieved room-temperature conductivities of ~10⁻⁴ S/cm. Gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) add a small amount of liquid plasticizer or solvent to swell the polymer matrix, boosting conductivity further but slightly reintroducing the risks associated with liquids. Novel polymer chemistries, including polycarbonates, polysiloxanes, and single-ion conducting polymers, are also being actively explored to improve room-temperature performance and lithium transference numbers.

Halide-Based Solid Electrolytes

Halide-based solid electrolytes represent a newer but rapidly advancing class of materials that have attracted significant attention since approximately 2018. They are composed of lithium combined with trivalent metal cations and halide anions (F⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, or I⁻). Their defining advantage is an exceptional electrochemical oxidative stability, often exceeding 4 V vs. Li⁺/Li, which makes them directly compatible with high-voltage oxide cathodes such as NCM (nickel-cobalt-manganese) and NCA (nickel-cobalt-aluminum) without requiring additional coating layers.

Li₃YCl₆ and Li₃YBr₆

Lithium yttrium chloride (Li₃YCl₆) and its bromide analog (Li₃YBr₆) are the most widely studied halide electrolytes. Li₃YCl₆ achieves ionic conductivity of ~0.5–1 × 10⁻³ S/cm at room temperature and can be synthesized via simple ball milling of LiCl and YCl₃ precursors, followed by heat treatment. Li₃YBr₆ demonstrates slightly higher conductivity (~1.7 × 10⁻³ S/cm). Unlike sulfide electrolytes, halide electrolytes do not generate toxic gases upon moisture exposure, although they still require controlled manufacturing environments. Their reductive instability against lithium metal requires the use of an interlayer (such as a sulfide or polymer buffer) when paired with lithium metal anodes.

Emerging Halide Compositions

Beyond yttrium-based systems, a wide range of trivalent metals including indium, scandium, tantalum, and lanthanum are being explored as halide electrolyte cation frameworks. Li₃InCl₆ is notable for its moisture tolerance — it can be reprocessed from aqueous solution and still recover its ionic conductivity, a remarkable property that simplifies manufacturing. Fluoride-based halides offer even wider electrochemical windows but suffer from very low ionic conductivity. The halide electrolyte design space is broad, and machine learning-assisted materials screening is accelerating the identification of new high-performing compositions within this family.

Side-by-Side Comparison of the Four Types

The following table summarizes the key properties and trade-offs of each solid electrolyte type to help engineers and researchers identify the most suitable material for a given application:

| Property | Oxide | Sulfide | Polymer | Halide |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Conductivity (RT) | 10⁻⁶ – 10⁻³ S/cm | 10⁻⁴ – 10⁻² S/cm | 10⁻⁷ – 10⁻⁴ S/cm | 10⁻⁴ – 10⁻³ S/cm |

| Electrochemical Window | Wide (up to 6 V) | Narrow (1–5 V) | Moderate (~4 V) | Wide (>4 V oxidative) |

| Li-Metal Compatibility | Good (LLZO) | Poor (needs coating) | Good | Poor (needs interlayer) |

| Mechanical Nature | Brittle / Rigid | Soft / Ductile | Flexible | Moderately Soft |

| Air/Moisture Stability | Excellent | Poor (H₂S risk) | Good | Moderate to Good |

| Processing Temperature | High (>800°C) | Low (cold press) | Low (<200°C) | Low-Moderate |

| Maturity / TRL | High | High | High (PEO commercial) | Emerging |

Despite their diversity, all four types of solid electrolytes face common engineering challenges that must be addressed before solid-state batteries can achieve widespread commercial adoption at scale:

- Interfacial resistance: The solid-solid contact between electrolyte and electrode is inherently poor compared to liquid electrolytes that wet electrode surfaces conformally. Space charge layers, chemical interdiffusion, and volume changes during cycling all increase interfacial impedance, reducing power density.

- Lithium dendrite penetration: Contrary to early assumptions, solid electrolytes do not automatically prevent lithium dendrite growth. Dendrites can propagate through grain boundaries, pores, or mechanical cracks — particularly under high current densities. This remains a critical safety and cycle-life concern.

- Scalable manufacturing: Achieving dense, thin, defect-free solid electrolyte layers at manufacturing scale is non-trivial. Ceramics require high-temperature sintering; sulfides demand strict dry-room conditions; polymers face pinholes and creep under pressure.

- Cost reduction: Many high-performing electrolytes (LGPS with germanium, LLZO with tantalum) involve expensive or scarce raw materials. Translating laboratory results into cost-competitive cells requires either cheaper compositions or processing innovations that reduce material usage.

Hybrid and Composite Electrolyte Strategies

Recognizing that no single electrolyte type is optimal across all performance dimensions, researchers have increasingly turned to hybrid and composite electrolyte architectures. These strategies aim to combine the best attributes of multiple material classes while mitigating individual weaknesses.

One prominent approach is the bilayer electrolyte, in which a thin sulfide or halide layer is placed adjacent to the cathode for high conductivity and compatibility with high-voltage materials, while a polymer or oxide layer faces the lithium metal anode to provide chemical and mechanical stability. Another strategy is the organic-inorganic composite, where ceramic nanoparticles (LLZO, LATP, halides) are dispersed in a polymer matrix, creating a flexible film that benefits from the polymer's processability and the inorganic phase's high conductivity and stability. Samsung SDI, Toyota, QuantumScape, and Solid Power are among the companies pursuing distinct electrolyte strategies — with sulfide-based composites and oxide thin films being leading choices for EV applications. The competitive landscape reflects the reality that the "winning" electrolyte chemistry will likely be application-dependent rather than universal.

Which Solid Electrolyte Is Right for Your Application?

Selecting the appropriate solid electrolyte depends on the specific performance requirements, operating conditions, and manufacturing constraints of the target application. The following guidance provides a practical starting point:

- Electric vehicles (high energy density, fast charging): Sulfide-based electrolytes (Li₆PS₅Cl, LGPS variants) are the leading choice due to their high room-temperature conductivity and cold-pressability. Halide electrolytes are gaining traction for cathode-side use. Companies like Toyota and Panasonic are focusing on this direction.

- Stationary energy storage (cost-sensitive, moderate temperature): PEO-based polymer electrolytes operating at 60–80°C offer a commercially viable, low-cost option. Bolloré's existing fleet deployments demonstrate real-world feasibility for grid and fleet applications.

- Thin-film microbatteries (IoT, medical implants, wearables): LIPON remains the gold standard for thin-film applications where energy density per area matters more than volumetric capacity, and where extremely long cycle life and biocompatibility are essential.

- High-voltage cathode systems (NCM811, NCA, LNMO): Halide electrolytes (Li₃YCl₆, Li₃InCl₆) and oxide electrolytes (LLZO, LAGP) are best suited due to their wide oxidative stability windows, avoiding the need for protective cathode coatings.

- Flexible and wearable batteries: Polymer and composite polymer electrolytes offer the mechanical compliance needed to withstand bending and deformation cycles, making them the only viable option for truly flexible power sources.

English

English Deutsch

Deutsch Español

Español 中文简体

中文简体